Rethinking food

Reading the horror story of ultra-processed food has changed how I eat on walks and bike rides.

Shortly after I joined the Scouts, my troop went on a hike in Bannau Brycheiniog. Along with the kit list the leaders issued were instructions that we should bring snacks for the traditional 'Mars bar stops' along the walk. My 11-year-old self took this literally, brought a whole pack of Mars bars and duly ate one every time we stopped for a breather.

My snack-often approach to fuelling a ride or walk has changed little since that time, but now I am increasingly focused on avoiding ultra-processed food (UPF). Essentially, this is stuff – it doesn't really deserve to be called food – that's sold in bright packaging and contains ingredients you wouldn't find in your kitchen at home.

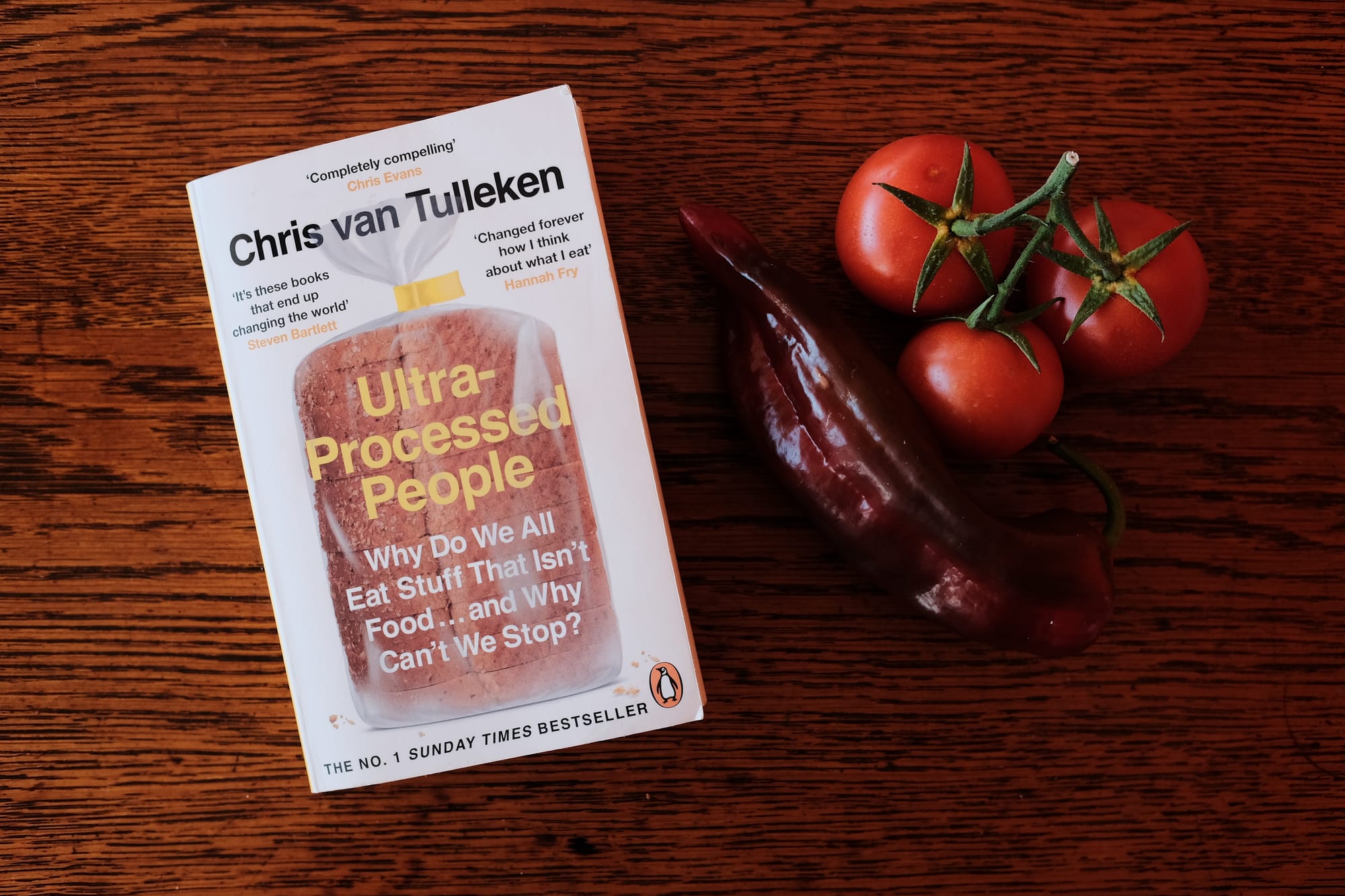

Take Mars bars, for example. Mars Wrigley markets its eponymous bar as 'a delicious fusion of chocolate, caramel and nougat'. But what this actually means is that you're eating things like glucose syrup, whey powder, palm fat and soya lecithin. As Chris van Tulleken explores in his book Ultra-Processed People, these sorts of ingredients combine to trick our brains. They disrupt the normal regulation of appetite and cause us to over-consume unhealthy products.

In 2024, the world's largest review of evidence on the impact of UPFs found that 'greater exposure to ultra-processed food was associated with a higher risk of adverse health outcomes, especially cardiometabolic, common mental disorder, and mortality outcomes'. And beyond the impact on health, van Tulleken argues that UPF also 'damages human societies by displacing food cultures and driving inequality, poverty and early death, and that it damages the planet'.

Around the world, communities used to grow, cook and eat healthy food sustainably. Now the food industry has taken over – using intensive farming, often in fragile environments, to acquire cheap ingredients for their unhealthy products. Heavily promoted and now cheaper than healthy alternatives, these products have come to dominate the market, leaving many people with no choice other than to buy and consume them.

Even if you know all about these health, social and environmental downsides, it's hard to stop eating UPF. Literally. This stuff is designed that way: soft, quick to eat and moreish. I hate everything it stands for but I still consume it, sometimes tipping a bag of Skittles (another Mars Wrigley product) into the back pocket of my cycling jersey on a longer ride.

But now I'm much more aware of what I'm doing and the fact that I've been played by the marketing. "Look at our bright colours," those Skittles called to me in the shop. "Imagine our tangy flavours, feel the joy of chewing us." You don't get that sort of chat from a carrot. A carrot promises the chore of peeling and the hassle of preparation; the Skittles promise you'll taste the rainbow. And who doesn't want to taste the rainbow?

Chris van Tulleken, Ultra-Processed People

Having had my eyes opened, I try to cook more of our food and snacks from scratch. Morning porridge fills me up way more than cereal ever did. The slow cooker has replaced fast food takeaways. And for walks or bike rides, I'm building up a decent repertoire of bake and no-bake bars and flapjacks, as well as other treats. My new favourite: nuts roasted in maple syrup with a dash of salt and cinnamon.

As the food industry fights back and tries to discredit claims that UPF is unhealthy, I keep in mind the advice of food writer Michael Pollan: eat real food, not too much, mostly plants.

Plus a Skittle or two from time to time, because nobody's perfect.